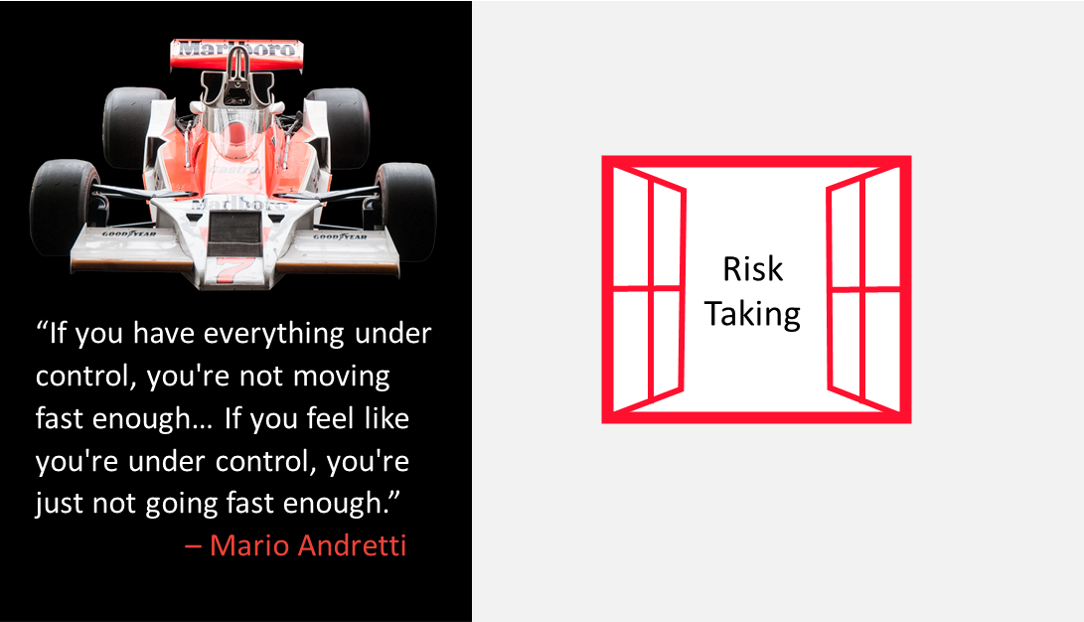

A Quote is a Concept-AnswerWhen I was in high school, I bought a book of famous quotations at Borders Bookstore. I’ve always been fascinated by quotes. Successful communicators use quotes during presentations, on their website, or during a coaching session with a client. A quote is a type of answer, but in AQ terms, which answer type is a quote (story, metaphor, theory, concept, procedure, or action)? Before I answer this question, let me take a step back to discuss answers in AQ terms. There are six answer types (again; story, metaphor, theory, concept, procedure, or action) and any other type of answer can be mapped to these six answer types. If you were asked for an “example”, this could be mapped to all six answer types. If you are asked, “Can you provide me an example of how a customer implements your software?” this could elicit a procedure-answer. Or, if asked, “Can you give me an example of customer success?” this could elicit a story-answer. An example has a one-to-many relationship to the six answer types, potentially representing all six answer types depending on the context and framing of the question. Therefore, it is important for a communicator to get the form of answer correct when an example is asked for. In similar terms, a quote has a one-to-many relationship to the six AQ answer types. However, it is my belief that a quote has a primary mapping to a concept-answer. For example, when I teach students in the classroom, I often share this quote from famed Indy car driver Mario Andretti… “If you have everything under control, you're not moving fast enough… If you feel like you're under control, you're just not going fast enough.” I share this quote to locate the concept of “risk-taking” for a student body that is often risk averse. I want them to understand and believe in the concept of risk-taking. In the classroom, or in business, as communicators we believe in important concepts, and we can communicate those concepts directly to others by using a definition. I could have defined risk-taking for my students. However, I’ve never seen a student read a definition and get animated with belief. Unlike a definition, a quote can inspire. The source of inspiration from quotes is two-fold. First, the source of the quote has credibility as an authority figure. Mario Andretti was a world class driver. In similar terms, at a client site when you give a sales presentation, a quote from a large Fortune 500 company provides credibility. Second, a related point, the credibility emanates from the experiences of the quote source. It is not hard to imagine that Mario Andretti has direct knowledge of risk taking. Or in the context of a sales presentation, credibility goes up if the Fortune 500 quote source is from an industry that is the same as the prospects. If the quote source and prospect firm is from the same industry, the experience base is similar, giving credibility to the quote. In summary, the Mario Andretti quote is a “window into a concept.” The concept of risk-taking is understood based upon source credibility and source experiences. Leadership QuotesTo further illustrate quotes-as-concepts, let’s examine a subset of the top 100 leadership quotes as identified by Inc. I will choose 3 quotes to make three points. First, quotes are concept-answers. Second, quotes are based upon credibility/experiences. Third, a new point, each concept associated with a quote can evoke different “dimensions” of the concept of leadership.

Let’s examine three quotes to illustrate from the Inc.com top 100 list: Quote 1: "The quality of a leader is reflected in the standards they set for themselves." – Ray Kroc Quote 1 evokes the concept of “quality” and Ray Kroc is a source of credibility because he built the McDonald’s restaurant system into what it is today by focusing upon repeatable standards and methods to develop a uniform quality experience every time for a customer. Quote 2: "Becoming a leader is synonymous with becoming yourself. It is precisely that simple and it is also that difficult." – Warren Bennis Quote 2 evokes the concept of “authenticity” and Warren Bennis is a source of credibility because he was a Professor at the University of Southern California (USC) often credited as the founder of modern leadership studies. In short, he studied the best leaders in the world; his experiences with those leaders give him credibility. Quote 3: “A leader is best when people barely know he exists. When his work is done, his aim fulfilled, they will say: we did it ourselves." – Lao Tzu Quote 3 evokes the concept of “empowerment” and Lao Tzu is a source of credibility because he was an ancient Chinese Philosopher who founded Taoism, and a deity in traditional Chinese religions. In a sense, leadership is too big of a concept to reduce to one quote -- that is why Inc compiled 100 leadership quotes. The point is that leadership is multi-dimensional. In the three quotes above, I evoke three sub-dimensions of leadership: quality, authenticity, and empowerment. At the extreme, the 100 quotes could represent 100 dimensions of leadership. In practice, a content analysis of the 100 quotes would reveal several repeated concepts. In social science, a “factor analysis” is a statistical process to reduce the number of dimensions of an overall concept into a parsimonious subset. Looking at quotes does not lend itself to a statistical factor analysis, but the point still stands that the dimensions of leadership quotes can be reduced to a smaller list of concepts. Building upon the prior paragraph, the final point regarding quotes and concepts is that quotes are often effective at locating to the multitude of sub-dimensions of a concept, to point out to an audience that a specific sub-dimension (such as quality, authenticity, and empowerment for overall leadership) deserves our attention. If you found Answer Intelligence (AQ)® an interesting framework, please share this post with others.

1 Comment

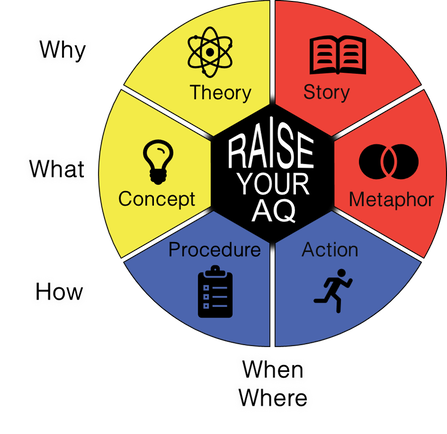

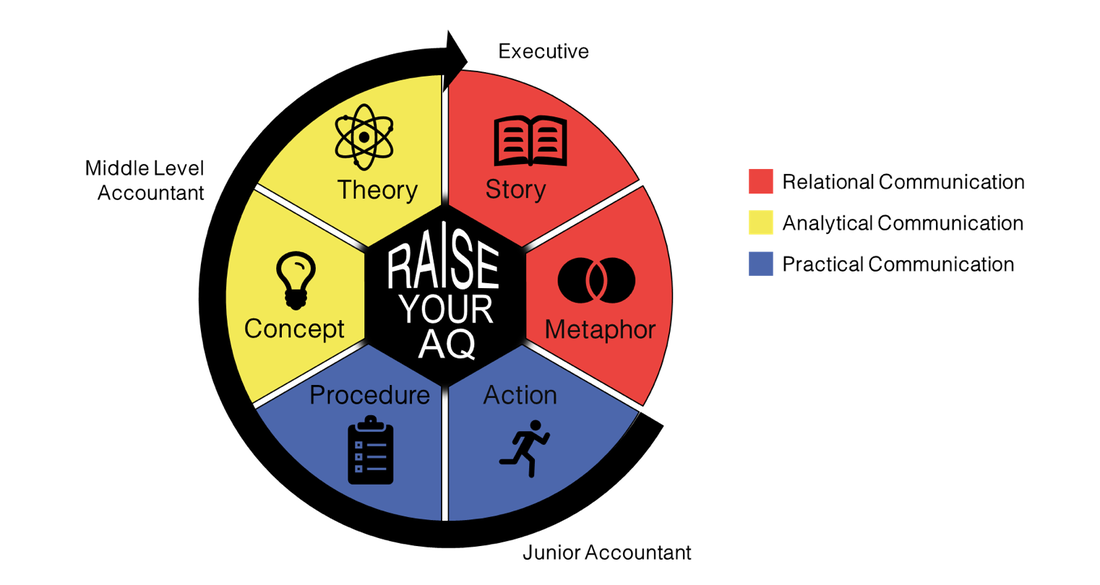

Mike Soenke is an Executive in Residence at North Central College (Naperville, IL, USA) and retired DOW 30 SVP and USA CFO. In this two-part series, Mike and I discuss Answer Intelligence (AQ)® based upon his experience as a former executive at a DOW 30 corporation. The focus of this blog post (2 of 2) is using AQ to elevate your career. The prior post focused upon using AQ to elevate your organization. The following interview is edited for clarity. This article is part of the High AQ Interview Series where executives, academics, and thought leaders discuss elevated answers. Using AQ to Elevate Your CareerDr. G: “As you look at the Answer Intelligence (AQ)® framework, can you describe its significance to a finance professional?” Mike Soenke: “The single biggest opportunity related to a leadership competency throughout the finance function was the ability to influence key stakeholders. AQ is an influence framework.” Dr. G: “When you were U.S. CFO of a DOW 30 organization, can you discuss how finance professionals typically improved their ability to influence over time?” Mike Soenke: “Out of college, finance staff are technically proficient doers. In AQ terms, they focus on the practical style (procedures and actions). A lot of finance staff can communicate in blue [the practical style] describing the financial standards guiding their work. When better finance staff progress, they start to work with people across the business … if all they can do is recite the standards they will not go very far… a lot of business people will get frustrated. For example, a business person may say, ‘I don’t understand why we can’t do X, Y, or Z to recognize more revenue.’ Better finance professionals will be able to get into the analytical skill and use concept and theory to clearly explain the purpose behind a standard and why it makes sense. Moreover, the more skilled communicators can translate finance into layman terms so that a non-technical person can easily understand. Theory and concept knowledge extends to business strategy and broader principles of finance as one progresses in finance. For example, a strong financial leader would proactively influence the right financial discipline: ‘We want to do X, Y, or Z to increase shareholder value… or we will not get the return that meets or exceeds the cost of capital so the enterprise value will erode if we make this decision.’ Relational communication, story and metaphor, is the capstone for financial and really all business leaders. As I mentioned earlier, finance is initially steeped in action and process [Practical style], and many can stretch to theory and concept, but only the expert level financial leader can excel at stories and metaphors to maximize their influence. For example, throughout my career I often had to influence independent franchise owners to support company initiatives through investment in labor, food cost, marketing or longer-term capital improvements. In addition to providing a data driven business case you often had to find a way to emotionally engage them with metaphors and stories of success to create system alignment. For example, I would often have a franchisee leader passionately share their story of customer satisfaction and financial success in support of the broader initiative … I wanted to pull people in and create enthusiastic system-wide support. There is a lot of skill in getting stories and metaphors right. While I preferred to use positive stories to inspire action, there were times when painting a negative picture of the future absent bold actions was equally or more impactful.” Answer Progression from Junior Accountant to Executive Dr. G: “You make a compelling case for a progression toward the relational style. Can you tell me a little bit about how an expert finance communicator, who has mastered story and metaphor, also weaves in the other answer modes?” Mike Soenke: “Of course, as I’m telling the story, I’m weaving in the theory and concept, and I would discuss procedures and actions associated with the story that a franchisee executed against to achieve success. Therefore, one story can be a touchstone for all the other six answer types. A skilled communicator can start with procedures... outlining the rules were not followed, and then pivot to a story of failure to drive home the consequences of not following the rules. Also, an effective story must be constructed to support your theory and concepts. For example, if there are three initiatives [key strategies; or concepts/theories in AQ terms] I might emphasize the synergies in emphasizing all three initiatives at the same time in the story, to inspire them to go after all three to generate incremental cash flow to make customers happy.” Dr. G: “Why do you think all finance professionals are not able to be effective relational communicators (using stories and metaphors)?” Mike Soenke: “Two things. First, people gravitate to a field like finance, or software development, because they are more technical in their knowledge base. Finance professionals are more introverted and communicating with stories and metaphors does not come naturally to many. This means individuals are more comfortable in the practical style of communication. Second, during my career, finance professionals did not have a thought framework to build out the different communication skills. Yes, we knew stories could be effective to engage, and we had an inventory of metaphors, but we did not have an organizational framework to make sense of all six answer types and map these answers to questions. In addition to an organizing framework, we did not have a roadmap to build out our communication competency in a layered manner. Using AQ and the 5 practice areas, it is possible to build communication skills over time in a thoughtful manner." Dr. G: “You’ve discussed that finance professionals progress in their career from practical, to analytical, to relational influence. Does the sequence of progression follow this pattern outside of finance?” Mike Soenke: “For different functions, or even for specific individuals within finance, the sequence of progression could be different. It might be a given professionals can tell stories and metaphors, but they don’t have concepts or theories behind them, or the ability to execute with procedures and actions is lacking. Therefore, it is possible for the process to be reversed in certain professionals.” High AQ Takeaway: According to Mike Soenke, finance professionals (and other technical professionals) will first provide influence with practical communication (procedure + action). Then, those that progress in their career master analytical communication (concept + theory). Finally, those that aspire to become executives will need to develop relational communication skills (story + metaphor). If you found Answer Intelligence (AQ)® an interesting framework, please share this post with others.

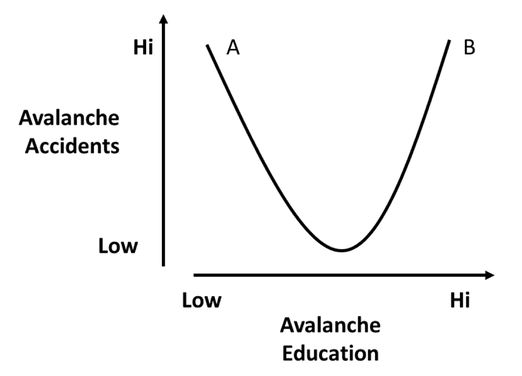

Chris Strouthopoulos is Founder & CEO of Ascent Empowerment Services where he provides mindset coaching and workshops to help individuals and organizations embrace challenge, overcome limiting beliefs, implement change, and achieve goals. The corporate logo for Ascent empowerment prominently features a mountain, a reference to his ongoing work as a mountain guide leading climbing expeditions around the world. On the mountain, or in your next business meeting, navigating answers can be the difference between success or failure. The focus of this article is to examine important questions (why, what, how) that the mountain asks of all climbers. Getting the answers right (story, metaphor, theory, concept, procedure, action) is the difference between life and death. This article is part of the High AQ Interview Series where executives, academics, and thought leaders discuss elevated answers. The following interview is edited for clarity. High Stakes Answers and Accidents on a MountainDr. G: “One can imagine that climbing a mountain asks questions (why, what, how) that evoke high stake answers (story, metaphor, theory, concept, procedure, action) that a climber must get right or risk death. What is the role of answers in accidents on a mountain?” Chris Strouthopoulos: “All accidents could be characterized as one of the six AQ answers. Sometimes the accident was a practical piece, a technical error, a procedure and/or action. A friend of mine died at Zion National Park because the rope was rigged incorrectly, a procedural error. The rope got cut and he fell to his death. Other times, theory or concepts are the cause of accidents. Take an avalanche… people who get killed in an Avalanche resemble a U-shaped curve that plots avalanche accidents and the level of avalanche education. Novice mountain climbers [see point A below] get killed because they don’t understand theory and concepts—they don’t understand the interplay of snow, terrain, and weather. They can’t judge complex hazards that can change minute by minute. Those expert climbers [see point B below] have the education but they have internalized the theory and concepts and are prone to cognitive errors when they over rely on emotion, or emotional decision making.” Dr. G: “Before we move onto accidents caused by metaphors and stories, it seems to me that procedures and actions are prone to errors when one goes on autopilot. Can you discuss guarding against intuition related to the procedures and actions of climbing?” Chris Strouthopoulos: “Absolutely. To prevent procedural accidents, go or no-go checklists are increasingly used by avalanche professionals. These checklists are modeled after the airline industry. Additionally, other procedural safeguards feature red, yellow, green lights… as you go through pre-climb, if you tally so many red lights, the climb is a no-go. Or, a combination of yellow lights, and a few red lights triggers the no-go threshold.” Dr. G: “Returning to story and metaphors, can you explain how one of these is a source of accidents?” Chris Strouthopoulos: “I was guiding a group of climbers on the Himalayas and stories can lead to success, reaching the summit. Or stories can lead to failure, death, or simply turning around when you could have climbed further. We were going after a 21K peak in the Himalayas, one guy trained for a year, he ran multiple marathons in preparation. He was the fittest person on the expedition, even at 60 years of age. The night before the summit, he started to imagine failure. He confided in me a story of his lack of self-belief and intimidation regarding the climb. And a 3rd of the way up on summit day he froze in his tracks. He was physically capable, and he knew the procedures and actions, but he mentally fell apart. Fear won. Fear is a concept [an answer in AQ terms], that had taken hold as a story in his mind. He told a story to himself of everything that could go wrong. This fear story was not consistent with the facts on the mountain. There were no objective failure threats; it was the best day of the season—no winds, perfect temp, no hazards. Unlike Everest, at this altitude, there is no death zone on the Himalayas. He built a narrative in his head that he was going to fail. In addition to the failure story toward the summit, an additional story takes hold that often pulls a climber back down the mountain. Climbers create a simple story around how comfortable it would be to have a beer and pizza at a lower altitude. The simple comforts of a comfortable restaurant represent an attractive story that pulls someone back down the mountain. The comfort story beats them. The failure story of climbing up beats them. It is really the collection of stories a climber tells themselves that most determines if they reach their goal- the summit - or not.” Taking the Mountain to the Business WorldDr. G: “The mountain evokes a heightened experience. Can you explain that for me?” Chris Strouthopoulos: “The mountain is so visceral, I can look down and see a 5,000 ft drop. The choice and consequences are so immediate, non-negotiable. Either I rope and start up the climb, or I don’t. Either I go for it on summit day, or I don’t. Even though the mountain is complex, it is also a radical simplification of the world, compared to what occurs in a typical business setting. On the mountain, the phone is not ringing, everything is just right to get into a flow experience.” Dr. G: “As you describe the mountain, it reminds me a lot of experimental design in psychology, the context in an experiment is stripped of non-essential elements, and only the key elements of a context that influence the experiment. In a similar way, mountain climbing evokes positive constraints that allow for these amazing experiences. How do you translate the experience on the mountain to the seemingly more mundane day-to-day in the business world? Chris Strouthopoulos: “I simulate the heightened context of the mountain, when I consult with my clients off-mountain on Zoom calls. Today I was onboarding a new client and I set up a challenge for him and he responded to this challenge. His response demonstrated his indecisiveness, he was paralyzed and withdrawn. His response to the challenge exercise mirrored how he has responded to divorce 4 years out. In the Zoom call challenge, he had a real experience, a realization of his indecisiveness that he could not have had if he read an article I assigned to him.” Dr G: “In AQ terms, High AQ practice 5 is Answer in Context, which recognizes that there are key elements of the context that influence any primary answer. In other words, as a coach you revealed the concept of indecisiveness by structuring the context in a way that revealed the indecisiveness. Can you tell me more about how you actively structure context that to create these high-quality experiences with clients? Chris Strouthopoulos: “When I was doing face-to-face training [prior to COVID-19] I would create challenges for a group where I would give them supplies, such as a blind fold, and clear tasks, with outcomes that were impossible to achieve individually -- success was only possible when they worked together. I designed the context, where they would have a great experience. I was able to approximate a mountain climb where the context is so immediate and pressing, stripped away of distractions that dilute or take away from the potential of a heightened experience. Now when I do Zoom calls [during the COVID-19 pandemic] I will send clients materials in the mail and during the Zoom call we are able to create realistic challenges. In coaching when context is done properly, it simulates the mountain. The context pushes down upon the climbers, so every answer is heightened. On the mountain, I learned how to dance with fear, talk to myself to go forward, rather than recoil from challenge. Off the mountain, the need to overcome fear is manifested in different ways, in underperforming areas of life… a bad divorce, or not speaking up at a meeting. When coaching is done properly, my clients can reach up and touch the context, which pushes back down upon them to reveal the answers they need to be successful. In this manner the mountain experience is brought to the board room, sales meeting, or anywhere they need to navigate.” This article suggests at least two High AQ Takeaways. High AQ Takeaway 1: On the mountain, or in business you are faced with three important questions (why, what, and how) that can be answered with six answers (story, metaphor, theory, concept, procedure, action). The wrong answers on the mountain can mean life or death. In your most important conversations in business, the wrong answers can hold you back from success and thrust you into your biggest failures. Work to get your answers right to reach the summit in your most important business conversations. High AQ Takeaway 2: High AQ practice 5 is Answer in Context. All six answers are revealed because of a pressing context. On the mountain, the context is salient, and every answer is revealed for being effective -- or not. In everyday life, the phone rings, we are distracted, and the effectiveness of our answers can be lost upon us in a context that is diluted. Chris Strouthopoulos teaches us to “reach up and touch the context” and feel it “pushing back” upon us during our most important conversations. When the context presses upon us, it is an opportunity to discover the answers to close the sale, the answers to get a job, or the answers to persuade the board of a new proposal. Identifying the pressing context takes effort and skill. Chris does this in his coaching, but we can all look to identify the aspects of the context that press down upon us. For example, in your next team meeting, ask yourself what element(s) in the context are most important? Perhaps, the context will be hiding in plain sight–a recent lost client; or the context is revealed through a shared story that has assumptions that have never been questioned. The mountain presents a visceral context in which right and wrong answers stand out. As we navigate the business world and have conversations with others, we should seek to bring the context close to us, pressing upon our most important conversations to help us identify the right answers. If you found Answer Intelligence (AQ)® an interesting framework, please share this post with others.

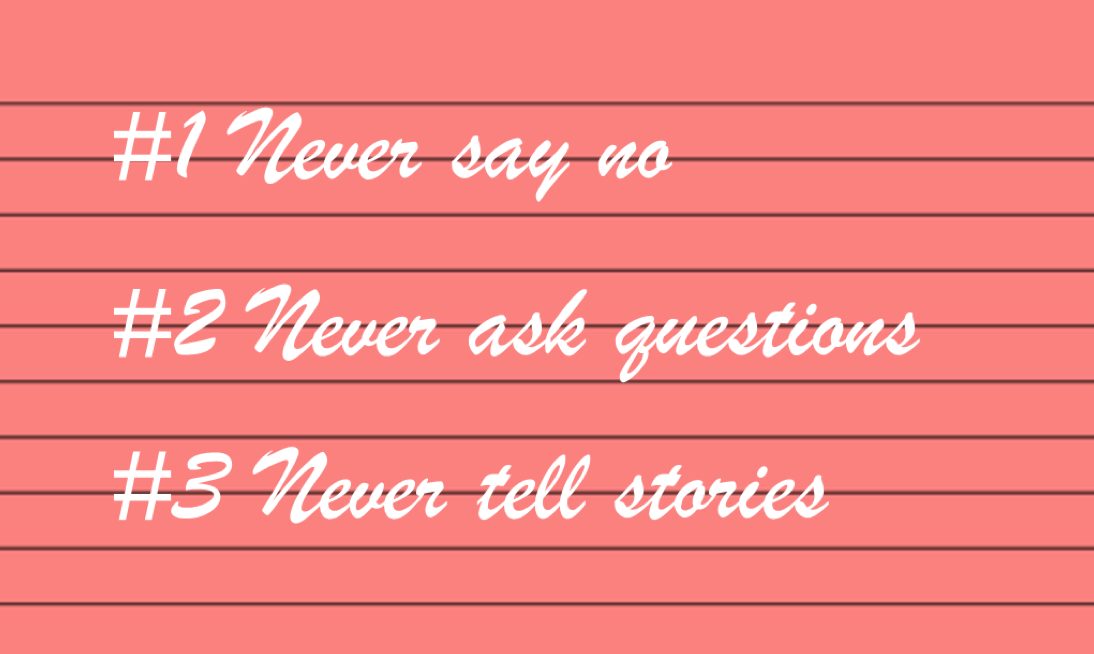

Bob Kulhan started off in improv when he was 19 years old in a summer intensive at the Players Workshop of The Second City. In 1993 Bob fully graduated from the Players workshop and from 1994 to 2009 performed improv and sketch comedy at the highest level, in all the three greater theatres—iO (Improv Olympic), Annoyance Theatre, and Second City. Since the 1990s, Bob has taken comedy improv to business with his book Getting to “Yes and”: The Art of Business Improv, as CEO of Business Improv, and to the business classroom as Adjunct Professor at Duke’s Fuqua School of Business. This article is part of the High AQ Interview Series where executives, academics, and thought leaders discuss elevated answers. The following interview is edited for clarity. Conversations and Improv: Let’s Get 3 Things StraightDuring our videoconference interview, Bob showed off a handwritten red notecard from 1993 that his mentor Martin de Maat had given him with three foundational rules of comedy improv. #3: Never tell storiesAll three of these points have implications for conversations in business. Starting with “never tell stories” (#3), this is perhaps the most counterintuitive point from a conventional understanding of conversations. After all, when you think of a conversation, you think of telling stories… Bob Kulhan: “You don’t tell stories because improv occurs in the moment. Stories are in the past or future. Improv happens right now. In a scene with more than one person…you are taking someone out of the conversation.” According to High AQ Practice 1, there are six answer types in the Answer Intelligence (AQ)® that can be provided to questions—story, metaphor, theory, concept, procedure, action. Bob’s commentary about the role of stories, and its potential push away from presentism is interesting and in stark contrast to the default opinion among many that are interested to the AQ framework, who often gravitate to stories as an important type of answer. Dr G: "Does this mean story is not important in conversations?" Bob Kulhan: “When you are experienced, all three rules [on the notecard] can be relaxed.” Bob went on to elaborate that in less experienced hands, “a story turns into a monologue. You are taking someone out of the scene.” #2: Never ask questionsFrom a conversation standpoint, nothing is as sacrosanct as the role of questions in conversations. For example, in sales conversations, question-methodologies dominate. In going after a job, you can’t help but trip over lists of interview prep questions on the internet. Naturally, as someone who authored a book on the importance of answers, I recognized answers were not as prominent as questions, but my view has always been a balanced perspective that questions and answers were a marriage of equals. I was intrigued by rule #2. Dr G: "Given the perceived importance of questions in business and society, tell me more about this counterintuitive rule." Bob Kulhan: “You want to keep the scene going. A question deflects…it goes lateral. In contrast, a statement [an answer in AQ vernacular] provides information. You are not asking someone to provide information.” Dr G: “This is interesting. It reminds me of a sales conversation where the sales rep asks lazy questions. One can imagine, a probing, broad question, such as “What are your company’s goals for next year?” or “What keeps you up at night?” True, these questions could have their place, but if they are offered up at the wrong time (say the very first minute of a first meeting) or out of laziness (not doing your homework), they don’t provide very much information… I can see how they would cause the conversation to go lateral, as you put it.” Bob Kulhan: “Yes. That’s it. Again, when you are experienced, the rules can be relaxed. In the flow of a rich conversation, a question is a gift. Such questions provide information about what is missing and where the conversation should go.” #1: Never say noBob Kulhan: “The most important rules is #1 Never say no. This refers to ‘Yes and’” [at the center of his book title]. Bob went on to explain that “Yes and” refers to a central premise of improv, to keep the dialogue flowing. This further underscores the importance of flow in a conversation. Conversations are not a monologue, but an interactive dialogue—a process of turn-taking and shared responsibility. In summary, rules #1, #2, and #3 suggest two High AQ takeaways. High AQ Takeaway 1: In less skilled communicators, there may be a tendency to use questions in a clumsy manner or to overuse stories. This is counterintuitive, as both questions and stories are touchpoint assumptions regarding conversations. High AQ Takeaway 2: “Yes and” conversations respect that the point of a conversation (and improv) is to keep the flow going. Too many conversations lack flow, and more resemble monologues (where each side is eager to give their speech), not engaged in interactive dialogue. Improv and AQ: What do you think, Bob?AQ holds that that why-questions are answered with theory and story, what-questions are answered with concept and metaphor, and how-questions are answered with procedure and answer. Additionally, there are 5 High AQ practices that provide guidance on answering questions. These prescriptions provide flexible rules used to communicate. Nonetheless, I’m often asked to discuss how conversations (as question-and-answer exchanges) dynamically unfold. In short, I’m pressed to explain more about conversation improv. Accordingly, I was excited to ask Bob directly about improv and conversations to get his expert opinion. I gave Bob an overview of AQ and then asked him some direct questions. Dr G: “The 5 High AQ practices provide flexible rules of communication, but they require improvisation to know which specific answers to provide, in which order, over time. What thoughts do you have about Improv and AQ?” Bob Kulhan: “Improv on the stage is all about getting the reps in. It only becomes comfortable when you gain experience. AQ is like any learned skill such as bicycling, martial arts, knife skills in the kitchen, or improv—you only feel comfortable when you achieve unconscious competency. For any individual that is embracing improv while communicating you must be so comfortable to provide any of the six answers, and pivot from one answer to the next based upon the response from the audience (one-one-one), or one-to-many.” Dr G: “That is interesting. First, you develop your muscle memory, then you pivot to different answers as needed in the conversation. How do you know when to pivot?” Bob Kulhan: “In improv you make initiations and declarations. For example, in 3 sentences you can know what a scene is about. Imagine, I walk in and say, “I lost my job.” That is a strong declaration for how the improv and the scene might unfold. I would imagine the same is true for AQ and answers. You pay attention to where the conversation needs to go. To guide the comedians on stage they follow shared rules. For example, one rule is always make your partner look good. If you get it wrong, you have an accountability system…if you slip and become a ball hog [taking up all the attention on stage], you will hear from your peers later that you acted like a ball hog.” Dr G: “It seems to me that you are describing the rules of engagement in ways that are like the 5 High AQ practices. If everyone knows these communication rules, you can have effective conversations that move in multiple directions. For example, a how-question, such as “How does your product work?” implies two possible answers, a procedure and/or action. By understanding the rules of conversations, it acts like the rules of improv.” Bob Kulhan: Yes. I agree. High AQ Takeaway 3: Improvisation in conversation is based upon a foundation of practice. When you rehearse the 5 High AQ practices, you will have the confidence in yourself. And when all communication participants use AQ you will have a shared framework to hold each other accountable and be successful. Dr. G: “In improv and AQ you have these rules of engagement and you want to be spontaneous. It is very possible to get tripped up trying to walk that tight rope. When I prepare job candidates for interviews, they realize they need to provide the right answers, but some get very nervous after the AQ framework when they open themselves up to the many ways they can answer (that they had not considered before).” Bob Kulhan: “The danger of improv is getting in your head. Again, you must practice so the rules are unconscious. Then, you must listen to the declarations of others and then react. For example, if a declaration is made on stage, “Dad I’m sorry about the car”, you know you are the dad and should react to your child wrecking your automobile; you know the general direction of your next line. In interviews, the job candidate needs to relax and be in the moment and listen for the interview declarations. If not, you are missing the gifts being offered up. You are thinking too much. Now you are thinking about not thinking. Before you know it, you are in an alligator dance. Be relaxed. Know you’ll figure it out. Let’s just dance in real time.” Dr. G: “As you discuss listening and responding in the moment, it reminds me of expert communicators we studied to develop AQ. A hallmark of the best communicators was the ability to provide all the answers. To be comfortable providing any given answer, you must be comfortable in providing all the answers. For example, if you tell a great moving story to an employee about how to lead others, a natural follow up question might be, ‘How do I take that lesson to my next meeting?’ Such improvisation entails transforming the story knowledge into a procedure and/or action to address this how-question. During the original research, we coined the term renaissance communicators to refer to communicators that could provide all the answers. In my AQ TEDxGeorgiaTech presentation I discussed Steve Jobs as such a renaissance communicator. Accordingly, in AQ and improv (at the highest level), I suspect there are no shortcuts. To be an expert at AQ you must know all the answers." Bob Kulhan: "Absolutely, there are no one trick ponies in improv. Additionally, nobody wants to do one thing. Usually, when they get pigeonholed there is a result… an emotional outburst. If you are the smartest person in the group, you don’t want to play the nerd every time, you want a chance to play the goof ball as well. Also, you must know how to pivot in real time if the dialogue is not working. I suspect the same is true for AQ, you must know how to pivot from one answer [type] to another to meet the needs of the conversation. In business conversations you need to know when a different type of answer is needed to move the conversation along. For example, a person explains a great procedure how to do something, and the conversation needs to shift to a great story, to hammer home why that procedure is important." High AQ Takeaway 4: A key to improvisation from any given answer type (e.g., story, metaphor, theory, concept, procedure, or action) to any other given answer type is to know all the answers. Those that aspire to provide improvisational answers during conversations with others need to embrace all six of the answer types. If you found Answer Intelligence (AQ)® an interesting framework, please share this post with others.

|

Access Octomono Masonry Settings

AuthorDr. Brian Glibkowski is the author of Answer Intelligence: Raise your AQ. Archives

October 2022

Categories

All

|

About AQ

Answer Intelligence (AQ)™ is the ability to provide elevated answers to explain and predict in a complex world, emotionally connect, and achieve results. Are you conversation ready?

Meet HarperHarper's story illustrates the transformative power of AQ in her own career and in the success of her organization.

|

AQ Upskilling PlatformAI is machine thinking. AQ is human thinking (developed based on academic research) in terms of simple questions (why, what, how, when, where, who) and answers (concept, metaphor, theory, story, procedure, action) that elevate human-to-AI and human-to-human communication.

|

Quick Access LinksBuy the Book

Explore AQ (Free Assessment) AQ TEDx Video Professional Services Firms + AQ Brian Glibkowski, PhD - AQ Creator Meet Harper - Overview Video Meet Mark - Software Case Reasons You Need AQ |

Featured |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed